|

|

Into The Ice: Glacier Bay |

||

|

||

The Park Service limits visits of big ships to Glacier Bay - you might see another ship, but it will be routed so that two aren't at the same glacier at the same time. This sailboat gives you a sense of scale here. |

|||||||||||||||||||

“This spacious inlet presented to our party an arduous task, as the space between the shores on the northern and southern sides, seemed to be entirely occupied by one compact sheet of ice as far as the eye could distinguish." This was English Explorer's George Vancouver’s Lieutenant Joseph Whidbey looking east to Icy Strait from near the entrance to what is today Glacier Bay. The Strait was completely choked with ice and appeared to be impassable. To the north, the bay was closed by “compact solid mountains of ice, rising perpendicularly from the water’s edge.” Glacier Bay didn’t exist; it was solid ice. A month or so after this discovery, Vancouver and his men finished their three summer exploration of the Northwest Coast and determined that there was no ice free Northwest Passage back to the Atlantic. They headed off to England around Cape Horn. And Glacier Bay disappeared into the mists of time for some 80 years. The Tlingits, of course, from the nearby village of Hoonah, and the Chilkats, hunted seals and had found that often the best hunting was on the very edge of the ice, where seals would often go to calve and nurse their pups. So it is very likely that during this period, if the ice had been receeding, they would have been moving north with it, setting up hunting camps in Glacier Bay, but leaving no written records. Then in 1877, an explorer, Charles Wood, seeking to climb Mt. St. Elias, entered a now much bigger Glacier Bay and noted he had to travel 40 miles to reach the ice front. While there, he stopped at a Tlingit seal hunter’s camp and recorded another bit of information that gives an insight to the ice’s rapid recession. The chief, around 30 years old, said that within his lifetime the whole area around them had been solid ice. This was startling: it meant that within that relatively short period of 30 years, 10 or 20 cubic miles of ice had disappeared. What caused such a great recession of the vast ice sheets during this period—some earlier version of global warming? No one really yet knows, but events in the late 1890s suggest substantial seismic activity in the Glacier Bay area. As these events were to prove, earthquakes seem to have the ability to shatter the ice in glaciers. Where such glaciers face the water, they will calve off immense amounts of ice after an earthquake, causing them to recede rapidly. The modern history of Glacier Bay really began in October of 1879, when John Muir, a noted naturalist and early preservationist, left Wrangell by canoe with a missionary friend, and three native paddlers. He had heard rumors of ice mountains in Alaska and had come to find out for himself. He had neither gore-tex nor fleece; his canoe was overloaded, and the route was one today’s kayakers probably wouldn’t even attempt at that time of year. They paddled west through Sumner Strait, up through Rocky Pass (Keku Strait) and across Frederick Sound to follow the west shore of Admiralty Island north. Their canoe was small, the waters big. When they’d finally crossed the choppy seven mile stretch of open water between Kuiu and Admiralty Islands, his chief paddler told him he hadn’t slept for days worrying about it. On they came, through Chatham and Icy Strait. As they traveled, the youngest native, Sitka Charley, told Muir he’d hunted seals as a boy in a bay full of ice and thought he could show Muir the way. Muir was skeptical. Sitka Charley said the bay was without trees and that they’d need to bring their own firewood. The other paddlers, in all their lives throughout the region, had never seen a place without firewood. They came to a bay cloaked in fog and storm. Sitka Charley became uneasy; the bay was much changed, he said, since he had seen it before. Even Vancouver’s chart, a copy of which Muir so much relied upon, failed them, showing only a wide indentation in the shore. Fortunately, they found a group of natives hunting seals and staying in a dark and crowded hut. One of the men agreed to guide them, and northward they paddled, off the chart and into that astonishing bay that had been birthed from the ice almost within their lifetimes. The weather got worse and Muir’s paddlers wanted to turn around: “They seemed to be losing heart with every howl of the wind, and, fearing that they might fail me now that I was in the midst of so grand a congregation of glaciers, I made haste to reassure them that for ten years I had wandered alone among mountains and storms, and good luck always followed me, that with me, therefore, they need fear nothing. The storm would soon cease and the sun would shine to show us the way we should go, for God cares for us and guides us as long as we are trustful and brave, therefore all childish fear must be put away.” —John Muir, Travels in Alaska

So on they went, camping in rain, on snowy beaches, pushing farther and farther, only glimpsing the vastness and grandeur of the land. Finally Muir climbed the flanks of one of the mountains just as the clouds passed, and he gazed, stunned, at the grandeur and the size of the many-armed bay that was revealed below him, full of slowly moving ice. When the party headed back, the lateness of the season was evident. Each morning before they reached Icy Strait, the ice was frozen a little thicker, and the men had to cut a lane for their canoe with an axe and tent poles. Muir’s description of his time in Glacier Bay are some of the shining icons of Alaskan literature:

“Then setting sail, we were driven wildly up the fiord, as if the storm wind were saying, ‘Go then, if you will, into my icy chamber; but you shall stay in until I am ready to let you out.’ All this time sleety rain was falling on the bay and snow on the mountains; but soon after we landed the sky began to open. The camp was made on a rocky bench beneath the front of the Pacific Glacier, and the canoe was carried beyond the reach of the bergs and berg waves. The bergs were now crowded in a dense pack against the discharging front, as if the storm wind had determined to make the glacier take back her crystal offspring and keep them at home.” —John Muir, Travels in Alaska After Muir’s discovery and powerful writings about what he’d seen, the bay soon became one of the premier sights of the Western Hemisphere, and a regular stop for steamers such as the Ancon, the Idaho, and the Queen. For many of the early steamer excursions, part of the trip was taking the ship’s boats to shore and if conditions permitted, taking groups to the top of the glacier itself to climb around amongst the crevasses! The destination was Muir Glacier, the face of which was an ice cliff towering above the decks of the approaching steamers and calving up to 12 icebergs an hour. “The Muir presented a perpendicular ice front at least 200 feet in height, from which huge bergs were detached at frequent intervals. The sight and sound of one of these huge masses of ice falling from the cliff, or suddenly appearing from the submarine ice-foot, was something which once witnessed was not to be forgotten. It was grand and impressive beyond description.” —Fremont Morse, National Geographic, January, 1908 The 1899 Earthquake—At midday on September 10, 1899, as he was waiting for lunch at his salmon saltery in Bartlett Cove, now site of Glacier Bay National Park headquarters, August Buschmann was surprised to see his trunk come sliding across the floor at him. Moments later, the cook’s helper came running into the building, frightened. He had been up on the hill at the native cemetery as the ground started to heave around him, and he thought the dead were coming to life. The earthquake shattered the front of Muir Glacier and others, and within 48 hours Glacier Bay was a mass of floating ice so thick that ships could not reach the saltery at Bartlett Cove for two weeks. Icy Strait filled with ice, making Dundas Bay, ten miles to the west, inaccessible. It wasn’t until the following July that the steamer Queen ventured close enough to Muir Inlet to see what had happened. The bay was still full of ice; only by picking their way along the shore west of Willoughby Island could they make any progress. The closest they could get to Muir Glacier was ten miles; the rest was solid ice. Hidden behind a fleet of icebergs, Muir Glacier commenced a rapid retreat up the inlet; today the face is 25 miles north of where Muir found it in 1879. Usually large cruise ships travel up the west side of Glacier Bay, often slowing or stopping to allow passengers a good view of Reid Inlet. Next to the north is the entrance to Johns Hopkins Glacier, very active in recent years, and the outgoing stream of ice is often so thick that ships often do not enter, for fear their propellors would contact ice pieces large enough to damage them. Additionally, seals use the ice flows in this inlet to birth their pups. During the period when they are actively birthing pups, ship traffic is prohibited here. However, while seal activity is the thickest in the inlet itself, you are apt to see seals, and perhaps even with their pups on ice flows anywhere in Glacier Bay, so be sure to have your binoculars ready whenever you leave your cabin in this area. Then most big ships will travel up and stop as close to Margerie Glacier and Grand Pacific Glacier as they can. In recent years there has been less ice here than John Hopkins, and ships are often able to approach fairly closely. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Glacier Bay has traditionally been a good spot to see humpbacks and other whales, so be sure to have your binoculars with you on deck and remember to keep a sharp eye peeled. Your ship will have a naturalist, but there may be whales that he or she doesn’t see. Another good spot for whale watching is Point Adolphus, Mile 1000, directly south of the entrance to Glacier Bay. Your Captain may query the local whale watching boats and if he gets a report of sightings there may take a loop through before continuing on his course. I was here in 1997 on the Dawn Princess when our Captain got a tip and, taking a loop through, spotted a group of humpbacks and let us ship drift, in hopes they might come closer. Regulations require big ships to keep a quarter of a mile away from whales, but in this case, after we stopped, the whales swam right over to us. I was on deck seven, the promenade deck, and had my camera handy as our fascinated group peered over the rail as the pod of five big humpbacks moved closer and closer until they were almost directly below where we were standing! I had seen humpbacks blow at a distance before, but this time they were close enough to hear their distictive ‘trumpeting’ when they exhaled after a long dive. This was actually too close as their breath was bad, bad, bad! Photo by Kay Gibson |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Glacier Bay is actually one of the best opportunities to see bears and goats from your ship. However, you will need the strongest binoculars you can lay your hands on! For bears, there are a couple of places to look. After about mid summer, there will be lots of berries on the slopes around the bay. So “glass” these hillsides carefully. What you will be looking for will be something that looks like a black spot that appears to be moving as it forages through the berry bushes. Another good place to look is along the shore, especially at low tide, as bears will forage for clams, crabs, etc. Mountain goats will be on the higher, steeper hillsides, and will be the white dots slowly moving!Look for bears both on the hillsides above Glacier Bay as well as along the shore. Photo by Ki Whorton |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Steamer Queen at Muir Glacier, about 1890. This graceful liner was one of the first to regularly bring visitors to Glacier Bay. Passengers could go ashore by small boat and climb ladders up to the top of the glacier. Imagine the Park Service allowing that today! Photo courtesy of Dave Bohn. |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

We were so young and foolish! Rowing around glaciers and icebergs is very dangerous - not only can they capsize without warming as the bottom melts and the center of gravity changes - see drawing below. But also a large iceberg calving suddenly from the glacier, even hundreds of yards away, could create waves that could easily capsize this tiny dingy.. Plus no life jacket!! |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

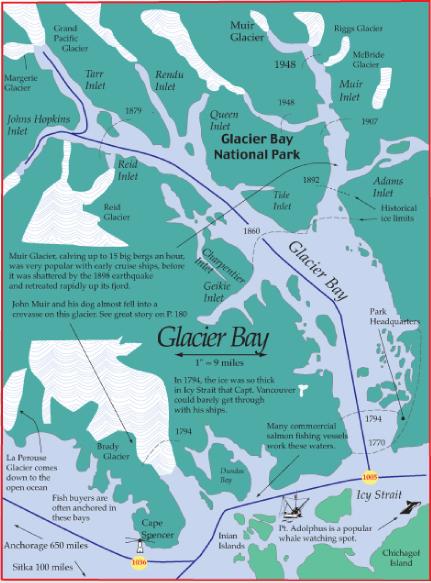

Glacier Bay today - actually this was from a 20 year old chart - the glaciers are actually substantially further back now. The amazing thing is that when English Explorer Capt. George Vancouver passed in 1794, there was no bay at all - it was a solid glacier all the way out to Icy Strait, which was so full of icebergs as to be almost impassable! |

|||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||

Calving glacier - look for areas of particularly blue ice, and splashes from small bits of ice falling into the water. Often these are precursors to an iceberg calving off the face of a glacier. |

|||||||||||||||||||